Introduction

When talking about sheet metal forming, many people associate this process directly with automotive or home appliance manufacturing. Fewer people realize that furniture is another industrial sector that makes use of shaped metal sheets, not only for internal and structural components such as hinges, handles, and drawer rails, but also for visible, aesthetic forms.

This type of production represents a niche market, often limited to a small number of pieces per year. At the same time, surface quality must be nearly flawless and capable of supporting sinuous, complex geometries. This combination creates a challenge that industrial designers and architects regularly face when translating conceptual ideas into physical products.

Charles and Ray Eames encountered these exact challenges throughout their careers, and this article also serves as a tribute to their work.

Who Were Charles and Ray Eames?

Charles and Ray Eames were born in Missouri and California, respectively, at the beginning of the last century. Their professional careers spanned architecture, art, painting, and industrial design, developing primarily during the evolution of American design following World War II.

Their work reflects a refined blend of American and Scandinavian design, an area in which Charles Eames had particular expertise. Eero Saarinen, the renowned Finnish architect and industrial designer, was among Charles’s closest friends.

Charles was an architect and industrial designer with a strong focus on materials, production, and technological aspects. Ray was an artist and painter, primarily concerned with aesthetics, spatial relationships, form, and ergonomics. By combining their complementary skills, they designed and produced numerous works that have since become icons of 20th-century design.

Their shared professional path, marked by close collaboration and a constant drive to experiment with new materials and production methods, led them in 1942 to sign an important contract with the U.S. Navy for the production of molded plywood components, ranging from leg splints to aircraft parts. Through this experience, Charles and Ray developed what would later become their distinctive design signature, which they applied to many projects, including one of their most renowned seating solutions, the Lounge Chair and Ottoman.

Eames Lounge and Ottoman (1956)

In 1946, Charles Eames was invited to the Museum of Modern Art in New York to present his first personal exhibition, featuring some of his most innovative seating designs. Following the exhibition, several American and European companies expressed interest in their work. Within a short period, Herman Miller in the U.S. and Vitra in Germany obtained exclusive rights to produce and sell Eames furniture in their respective markets. To this day, these remain the only two companies authorized to manufacture and distribute Eames products.

Eames Elephant: A Playful Legacy

“Toys are really not as innocent as they look. Toys and games are the preludes to serious ideas.” Charles Eames shared this thought during an interview, capturing a central principle of his design philosophy.

Guided by this belief, Charles and Ray, and later their office, designed numerous toys and pieces of children’s furniture. Among these was the Eames Elephant, a child’s seat shaped like a pachyderm.

In 1945, during experiments with molded plywood, a prototype of the elephant was produced and given as a gift to their daughter, Lucia. Mass production, however, never began due to the difficulty of manufacturing such flowing and complex shapes.

Only in 2017 did Vitra begin serial production of the legendary Eames Elephant, offering versions made from both plywood and plastic.

Reimagining the Eames Elephant: From Plywood Roots to Stainless Steel

There is a strong connection between the original Eames Elephant and the version presented in this article, namely the production method.

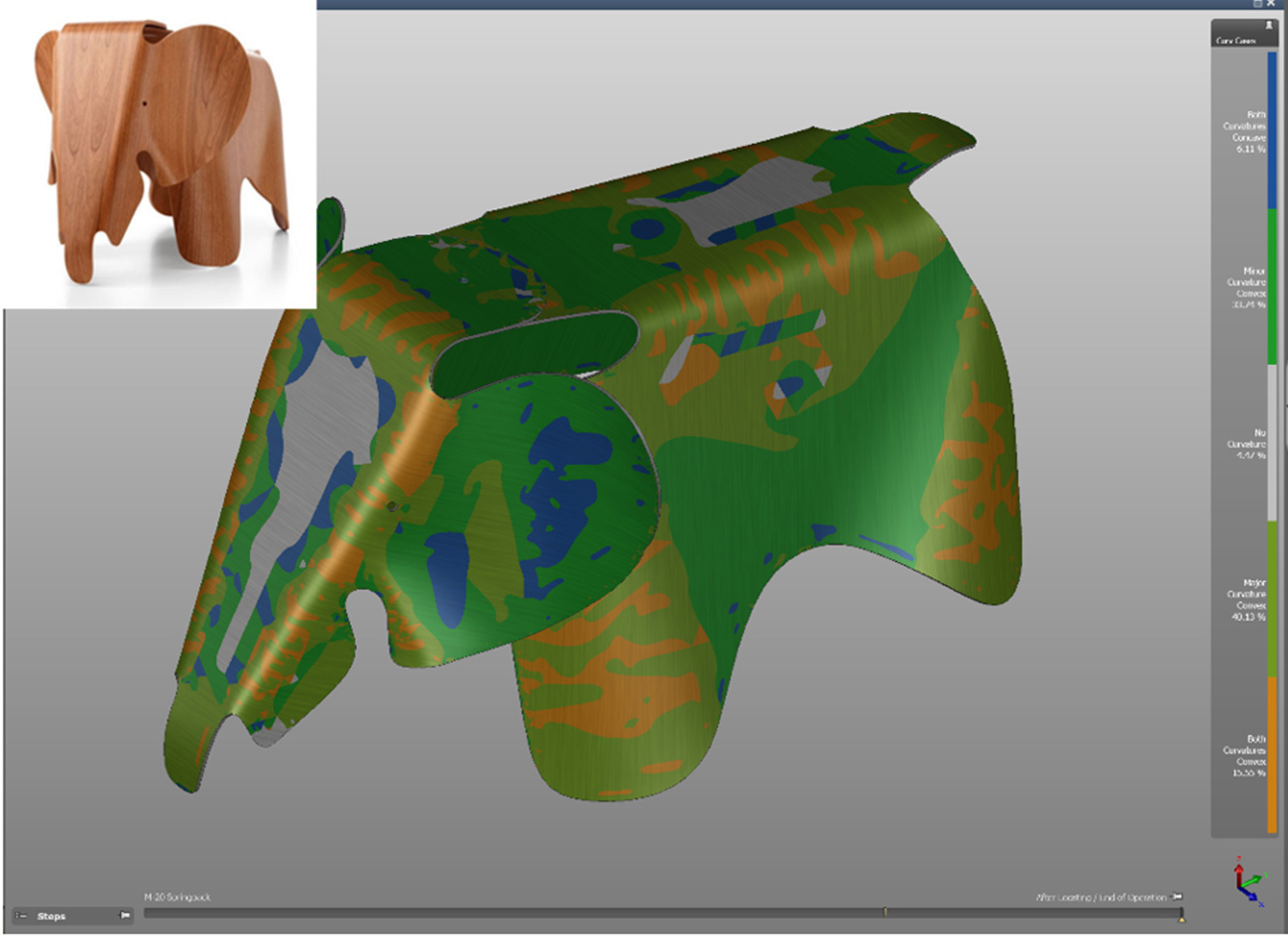

To create their wooden prototypes, the Eameses developed a self-made tool known as the Kazam!. This machine consisted of a mold in which plywood was shaped using a rubber balloon inflated with a bicycle pump. The same underlying principle is still used today for many sheet metal components produced in low volumes but requiring high surface quality. By replacing air with hydraulic fluids, this method has evolved into what is now known as hydroforming.

Concept 1: Sheet Metal Hydroforming

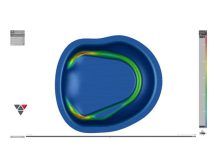

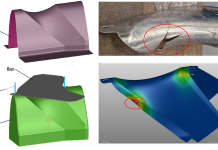

As a tribute to the Eameses’ ingenuity, we simulated the production of the elephant using stainless steel sheet metal, starting with a hydroforming process inspired by their original approach. As the Eameses themselves discovered decades ago through repeated trial-and-error experimentation with plywood, this path proved challenging. In this case, the difficulties were primarily related to the high forming depths and the instability of the sheet metal.

The Eames Elephant concept manufactured through sheet metal hydroforming

Concept 2: Progressive Die Stamping

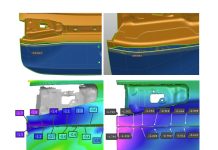

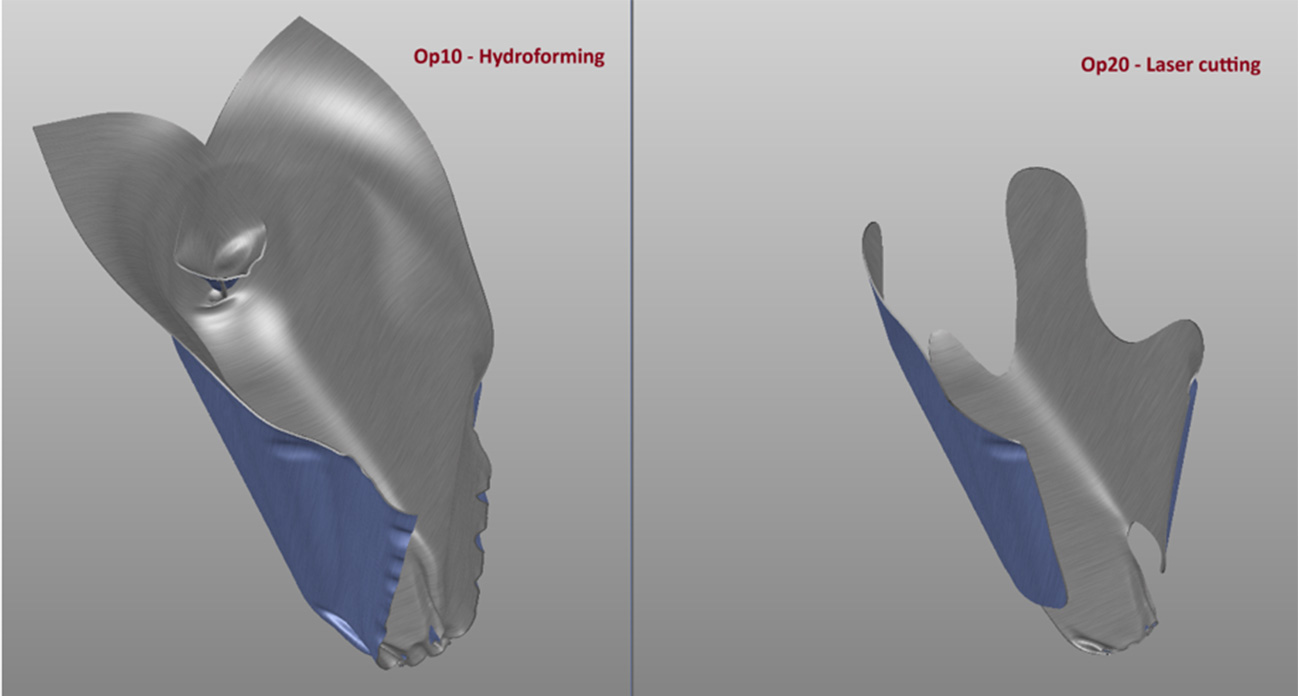

Using an alternative approach, both the head and body of the elephant were conceptualized and simulated using a progressive die stamping process consisting of seven operations. This configuration resulted in one complete part per press stroke, combining both head and body.

Figure: ProgDie setup for the concept manufacturing of the elephant head and body together in a single strip

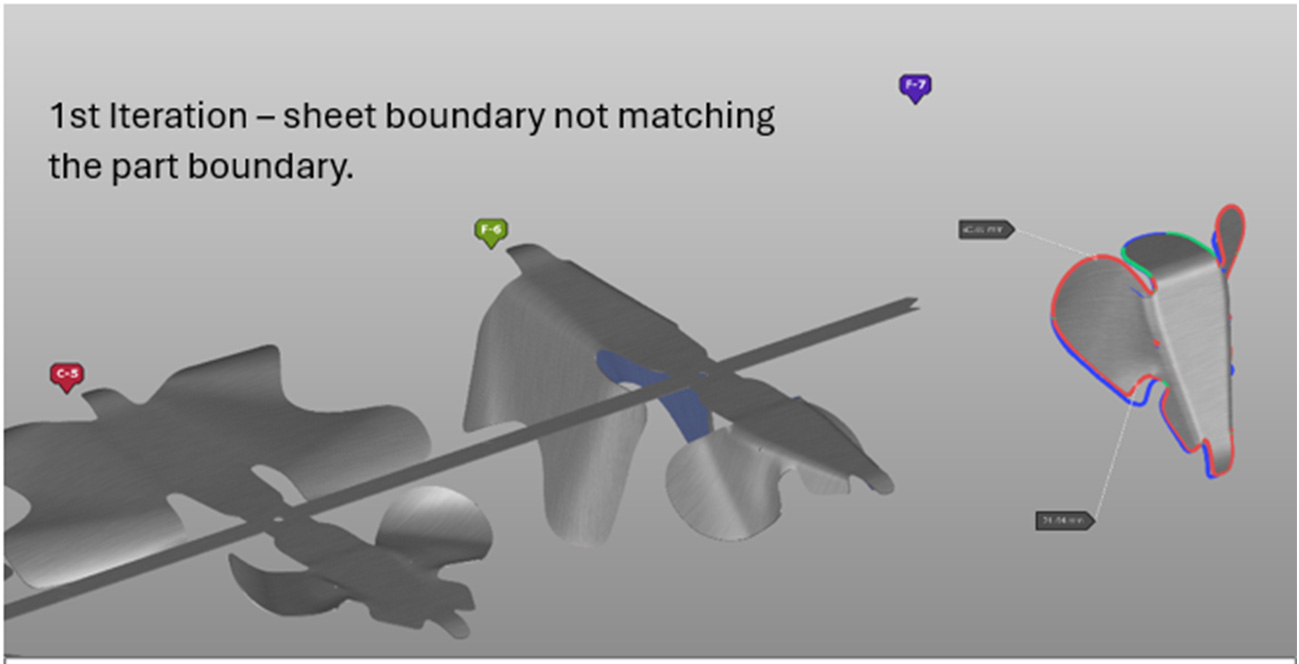

A trimline optimization was also carried out to bring the simulation as close as possible to real manufacturing conditions. The resulting part closely matches the intended outline, as shown by comparing the first and last trim optimization iterations.

Finally, the head and body were virtually welded together in AutoForm Assembly, resulting in a complete Eames Elephant made entirely of steel.

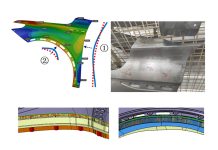

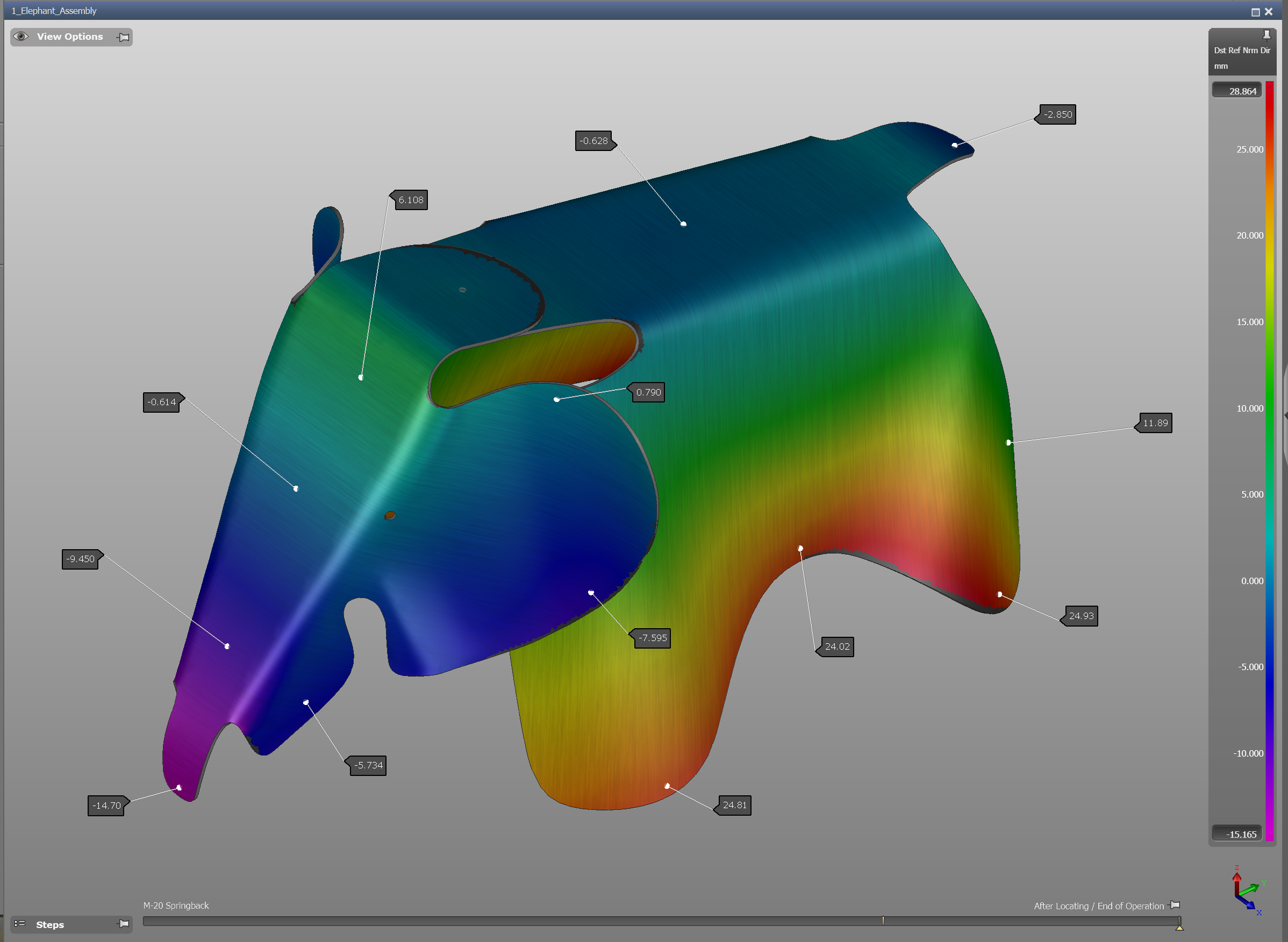

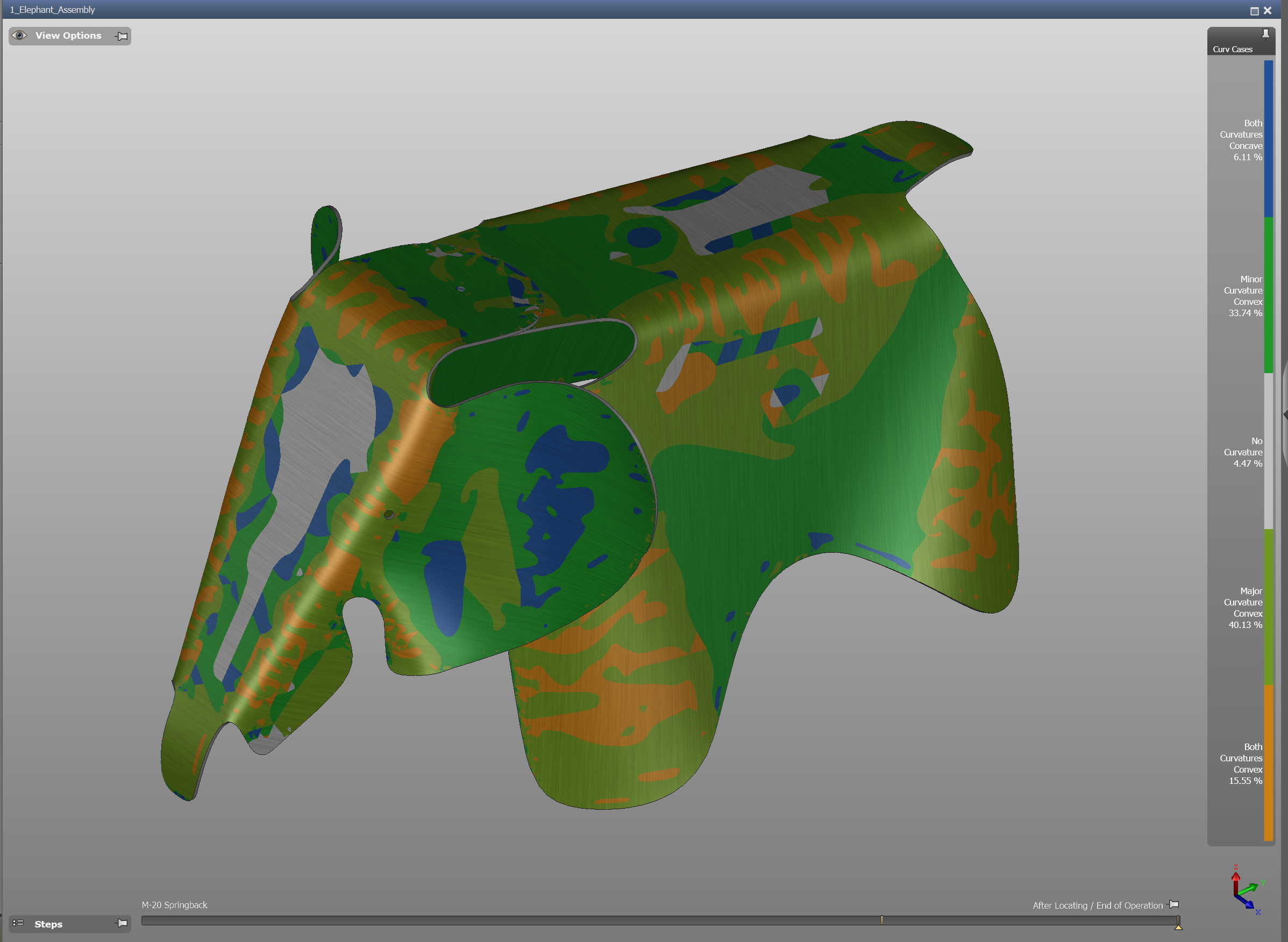

Springback in the Eames Elephant

Springback in the Eames Elephant

Imagining an Eames World with Today’s Technology

AutoForm software provides a comprehensive simulation solution not only for automotive and white goods applications, but also for other industrial fields such as furniture. These tools support designers and engineers in achieving higher-quality products while significantly reducing traditional trial-and-error loops.

If Charles and Ray had the chance to simulate their ideas before developing their production tools, it’s tempting to imagine that the Elephant, along with all the other animal seating prototypes they created, might have reached mass production much sooner. This could have offered children of the 1950s and 1960s more affordable and innovative toys to play with!